|

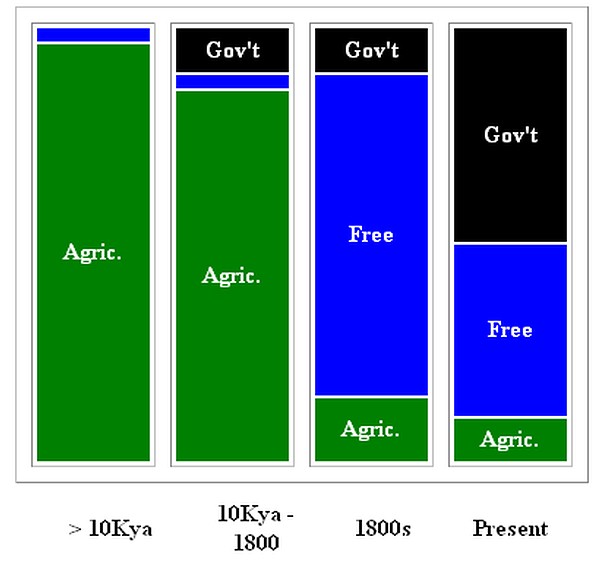

A Measure of FreedomQuite rightly, we tend to focus here mostly on what is happening today, rather than long ago. However, to do that all the time is a pity, for it robs us of historical perspective, which can be quite valuable. For example, consider: Are we more free today, than our forebears were in the 1900s? How can we tell? Does it matter? I think it may matter, because if we can measure changes in human liberty, we may be able to correlate them with other things that were going on then, and so deduce reasons for the increases or decreases in liberty over time. Then, knowing better the factors that cause more or less of it, we may be able to influence corresponding factors today to increase it here and now. So I offer a diagram of relative degrees of freedom at four different stages in human history.

It uses a form of the concept called "Agricultural Surplus." The thinking is that until we have enough to eat, all else is irrelevant; there is no life. Once we do have enough to eat, then we can talk about what happens to our spare time--the surplus. (Other definitions use the term to mean a literal surplus of food products, available for export etc.) The left-hand bar in the chart suggests that for the tens of thousands of years during which modern man was nomadic, eating each day what he could hunt or gather that day, there was virtually no agricultural surplus and therefore only a thin sliver of freedom; yes, a person could wander off and live by himself, but still he'd need to spend most of his day finding food. There was no writing during this era (though in Lascelles , France there were some amazing cave paintings) so we can't be sure, but it appears there was no government either. Then about 10,000 years ago mankind found a way to cultivate crops; that is, to stop wandering, live in one place, prepare the soil, plant seeds, harvest the food and store it for the winter. Dramatic lifestyle change! It probably happened first near Lebanon , and the idea quickly spread--though not to all parts. The news didn't reach Siberia , for example, or if it did the Siberians only smiled politely; for there was no soil for them to till. It was frozen year round and they lived on and with herds of reindeer before migrating, in due course, to America over the Bering bridge. From then onwards, mankind had some spare time. Not much, I guess, while planting and harvesting were in process, but at other times in the year he could lie back and smell the roses and apply himself to other creative tasks like building a home, digging a deeper well, designing better tools, weaving fancier clothes, engaging in trade and inventing the wheel: this was his agricultural surplus. Things were produced additional to food itself; capitalism had begun. Soon after that history-changing moment, writing was invented, and from earliest stone carvings there is evidence of government, so we deduce that settlement, writing and government all happened in a short space of time; less than 500 years, perhaps. There is no record of why government appeared, so we must speculate; Franz Oppenheimer in The State reckons one group of villagers decided to plunder their neighbors' crops because that seemed easier than planting and harvesting their own. Then without even blushing, they announced they would protect the survivors from marauders. In effect, governments stole the agricultural surplus, or much of it. The degree of freedom--the time an ordinary family had to itself, or to use to invest (plow back) for its own future--was no greater than it had been before the great discovery of agriculture; poverty remained endemic for another nine millennia, even while government people went on from one degree of luxurious living to another. The bigger the agricultural surplus, the more they stole and the more they wasted. The next big change came around 1800 AD. Then it was that agricultural science made its biggest breakthroughs. In less than a century and a half, at least in the "developed world," people migrated en masse from farms to factories because ways had been found to greatly boost the productivity of fields, while machines made it far less labor-intensive to plant and harvest. All this took place while the populations being supported and fed by those fields grew by leaps and bounds; in the USA it shot up from 5.3 million in 1800 to 76 million in 1900, helped much by immigration, but in the UK and much of Europe also, populations multiplied in that amazing century. The agricultural surplus suddenly exploded. But government did not explode, not during that 19th Century. Accordingly the degree of freedom increased far, far beyond any precedent. It was put to excellent use; inventions abounded, investment risks were taken and often rewarded, living standards shot through the roof, wealth multiplied and was spread widely throughout society--a whole middle class was created where none had previously existed. Why could this happen--why was government so slow to grow? Different reasons, as I see it. In the USA there was the Constitution, just recently set up. The Feds were eager from the get-go to push its limits, but when they lost a few early skirmishes like the Alien and Sedition Acts and the first two attempts to create a central bank, they knew their growth had to be gradual. In the UK , where this "industrial revolution" was actually taking place with greatest effect, the large agricultural surplus happened to coincide with a couple of generations of classical liberals in politics, who actually believed in limited government; an event so rare, we may call it unique. Prodded by such heroes as Cobden, Bright and Wilberforce, they actually repealed the Corn Laws (i.e., stopped trying to punish international trade) and abolished slavery, three decades before Lincoln did and without a drop of bloodshed; or more accurately, they withdrew from slavery the government support indispensable for its survival. The window was short--liberals had begun to cave in by 1870, when government schools were instituted in the UK , and fully of course by 1914 when they led the country into the disaster of WWI. But that short window allowed the flowering of all the glory of the Industrial Revolution. By 1900 government people realized what a vast opportunity they were missing and have not looked back since, in the urgent work of stealing an ever-growing agricultural surplus--so that now, even though it costs even less to feed the population, the degree of freedom is smaller than it was in the 19th Century; a smaller fraction of our decisions, and dollars, and minutes in the day, are ours to enjoy now than they were then. One simple proof: in 1910, US taxes took less than 10% of what people earned, in total. Today the grab is just under 50%. Government quintupled, in less than a century. So what does this measure--the agricultural surplus, and how much of it government steals--help guide us about how to increase our liberty? One answer might be that "we need to get back" to the days of small government, i.e. Constitutional Rule. Even if there were any credible, practical way to compel government to abandon four fifths of its power (there isn't), I disagree with that, on two grounds. First, if somehow it were successful it would merely place this society where it was in, say, 1825 or 1850; and that was the time after which all the obscene growth of government took place, despite the finest "limits" mankind had ever written. Why go back to a situation that history has already proven to be unstable? Why inflict on our grandchildren the miseries suffered by our great-grandparents? Then second, the 19th Century was indeed marvelous compared to all centuries previous--but it was not by any means ideal, compared to the standard of human liberty. There's a long list of outrages by government that polluted the 1800s, some of them featuring in works by Thoreau and Spooner, and most obviously including the savage slaughter of one American in every 60 in a totally needless government war. So my suggestion remains, instead, to point to the many positives of 19th Century freedom and insist that it be perfected by removing government from the scene altogether; for if partial freedom is that good, just wait till we enjoy it undiluted! As to the means for accomplishing that: if you haven't already joined, TOLFA awaits your attention and commitment. |