|

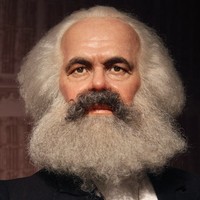

Labor's PriceThe wage due for a week's worth of unskilled labor today might be $464, and so it was two or three hundred years ago – though then, it was often called a “pound.” Of silver, that is. Is that to be fixed by law as the permanent value of such labor, or is it to be free to vary subjectively with demand, supply and quality? I hope that all readers will reply “the latter.” Some work better than others, sometimes the employer suffers a weak demand for his products, and sometimes he can barely keep up with that demand. He will want or need to pay less, or more, for labor accordingly. That's rather basic free-market stuff. But Karl Marx, whom Alex Knight recently described here as the “most evil” person ever to live, said the opposite; he proposed that labor can be valued objectively, that it has a fixed value regardless of market conditions and that such value attaches to the person laboring. On the principle that it's always a good idea to “know one's enemy,” it's worth examining his view. It does have a certain appeal. “Work is its own reward” is sometimes said, though tendering it at the checkout may not be too effective. But “if it's worth doing, it's worth doing well” is a fine principle, and the simple laborer in a large system such as a factory cannot easily judge the value of his contribution; he puts in a good week's work, and expects pay accordingly. Work, it may very well seem to him, has an inherent value, objectively. He cannot influence market demand for the products he helps make, any more than the weather; so why should such factors affect how much he gets paid? This is not just something with popular appeal, it does have a superficial appearance of being “fair.” Marx may have embraced it for both reasons. Now follow where it led him. Even if the idea of a fixed reward for a fixed amount of labor were modified so as to decree higher rates for specialists than laborers (e.g., neurosurgeons might get triple the basic rate), each of them would have to be prepared by experts and imposed by force of law. Deviants and cheats who contrived to pay more (or less) than the prescribed rate would have to be chastised. Marx saw all that, and his manifesto provided for it; the population was even to be “redistributed” so as to make labor resources available where the experts decided it was needed. Ultimately, if labor has a fixed value, its use must be micromanaged by a governing elite; work must be compulsory and it must be performed where directed. It leads us straight in to a Brave New World. And to help reach that utopia of fixed rates, in the meantime earnings were to be taxed “progressively,” meaning that the more you earn, the greater the rate of tax, not just the sum due. Quite deliberately, those paid over the approved sum were to be penalized. The US Congress continues to follow his advice. The President this winter repeatedly said that the rich “can afford a little more,” as if they were not already being selectively punished for succeeding in this country. Marx is alive and well in Washington, D.C. We can further understand Marx's mainspring by taking this logic a bit further. If labor has an objective value, and if all production comes from labor, it follows that workers (defined in some way) properly own all that they produce; that they are entitled to all its fruits. So if in some factory the profits come to one silver pound per worker per week but each is being paid only 0.8 pounds, somebody is exploiting him! Thus, the factory owners become The Enemy. I hope I've fairly represented the way Marxists think, and if so, I've shown why his Manifesto seems so bloodthirsty – that the progressive income tax was necessary “to crush the middle class under the guise of of a need to finance the government.” Of course; the middle class was parasitic, exploiting workers, living off their labor, The Enemy. So, crush the bourgeoisie! Any excuse will do! When he was not busy drinking, young Karl had, at the University of Berlin in the late 1830s, studied the philosophy of G.W.F. Hegel - whose contribution to human wisdom was to propose that man is happy only when fully identified with his community; when its aims are his aims, when he applies all his ambitions and energy and skill and life to its well-being. He even called that “freedom”! Hegel (1770-1831) with this state-idolizing philosophy had sprung to prominence under King Frederick William III, who, after his army's humiliating 1806 defeat by Napoleon, ordered that all children be schooled by the state to learn obedience to the state; his "Prussian school" system was what Mann copied and brought to America and is what we live with today. So both that and Marx's communism were triggered by Napoleon's rampage and plunder of Europe, which was occasioned by the spectacular failure to create a viable economy by the revolution in France, which resulted from centuries of domination by the aristocratic governors. The sequence well illustrates how governing (the use or threat of violence to impose rule) triggers new violence, which begets more violence, which . . . .

So when Marx decided labor had a fixed value and thus implied it should be directed, it was a simple step to blend that idea with his religious devotion to the supremacy of the community and conclude that property as well as labor belongs properly only to it, not to the individual; hence his aim to abolish private property and hold everything in common, i.e., “communism.” Murray Rothbard, in Requiem for Marx, has an extensive and amusing history of communism from its origins in the 1500s when certain “millennial anabaptists” of central Europe practiced common ownership in their communities for religious reasons (rather like the Pilgrims in their disastrous first year in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts) – and all of them foundered on two problems: (1) how to motivate anyone to perform work, since the products of labor went not to the laborer but to the common store, and (2) how to prevent the governing elite – needed to overcome that problem by directing labor and allocating food – from living a life of unegalitarian luxury. Those were never solved in Münster then, nor later by Marx in theory, nor later yet in Moscow in practice. It's easy for us to recognize the evil in the Manifesto itself, how it proposed violating the Self Ownership Axiom all over the floor. But once you grant the premise that labor has a fixed, objective value, it makes sense. Market anarchists sometimes express our feelings about the State in fairly lurid terms – because we recognize it as The Enemy; Marx supposed someone else was in that position, and wrote accordingly. “Evil”? Yes, but not beyond understanding, once we How can that faulty premise be corrected? By reference to the undeniable premise, that of self-ownership. Since each person owns his own life and person, he owns his own labor. Since he owns his labor, he has the natural right to exchange it at any rate he can agree with a buyer – who, likewise, has full control over the resources used to buy it. The value of that labor is therefore not objective or fixed, but entirely variable and subjective, determined from time to time in an ever-varying market by the principle of voluntary exchange. But alas, Karl Marx never embraced the self ownership axiom, any more than most modern economists do nor any more than all government people do, and so he drew grotesquely evil conclusions, just as they all do. Did he even know of the axiom? I'm not sure. Carl Menger was 22 years his junior, so the Austrian economic understanding would appear only after Marx had nailed his colors to the mast, as it were; if encountering them after gaining fame as a communist, very likely he would brush them aside, for nobody likes his premises disturbed. Marx lived in London after 1849, and so was right in the prime workshop of classical liberalism; one may fairly wonder if he could really have failed to notice something of its underlying philosophy and the dramatic way it was lifting people out of poverty. In the very next year, Bastiat, in Paris, wrote his The Law, and surely a self-professed economist and philosopher – who had also lived in Paris four years previously – would not neglect to study it. Did he even read Adam Smith? If he did so fail, or if he read such and rejected them, then--if not sooner--we can start to blame him. I think we can blame him also for being plain stupid, even if he was unable to access such works. If labor has an objective value such as a pound of silver per week, then it doesn't matter how the labor is applied; it's just as valuable whether it is devoted to cleaning streets or to digging a large hole and filling it up again. That is so bizarre as to be unworthy even of ridicule. Marx was not dumb; he should have seen that. Labor attracts whatever price a willing buyer finds to be currently worth paying; that much, and neither more nor less. It's subjective. It's often and rightly said that ideas have consequences, and that works both ways. Marx's erroneous idea that labor value is objective led, ultimately, to the massive worldwide slaughter cataloged in The Black Book of Communism, plus all the misery and deprivation – of working class people more than most – that sprang from the tight control of the Soviet state. Some have described Marx as an “idiot” more than “evil,” but what's for sure is that he got his premise wrong. So do government people of every flavor. Premises matter. |

Hegel's ideal is a transfer of worship from God to the State, and Marx swallowed it whole. As Rothbard rightly perceived, that's a true and passionate religious devotion. The sentiment – the primacy of the state over its subjects – is now found everywhere. In this country, for example, we hear chanted, “I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the United States of America, and to the Republic for which it stands . . . .” though the associated

Hegel's ideal is a transfer of worship from God to the State, and Marx swallowed it whole. As Rothbard rightly perceived, that's a true and passionate religious devotion. The sentiment – the primacy of the state over its subjects – is now found everywhere. In this country, for example, we hear chanted, “I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the United States of America, and to the Republic for which it stands . . . .” though the associated  see his root error. I really don't think Karl Heinrich got up in the morning, saw himself in the looking glass (he skipped shaving) and asked himself what new evil he could do that day. Like government employees who haven't yet read

see his root error. I really don't think Karl Heinrich got up in the morning, saw himself in the looking glass (he skipped shaving) and asked himself what new evil he could do that day. Like government employees who haven't yet read